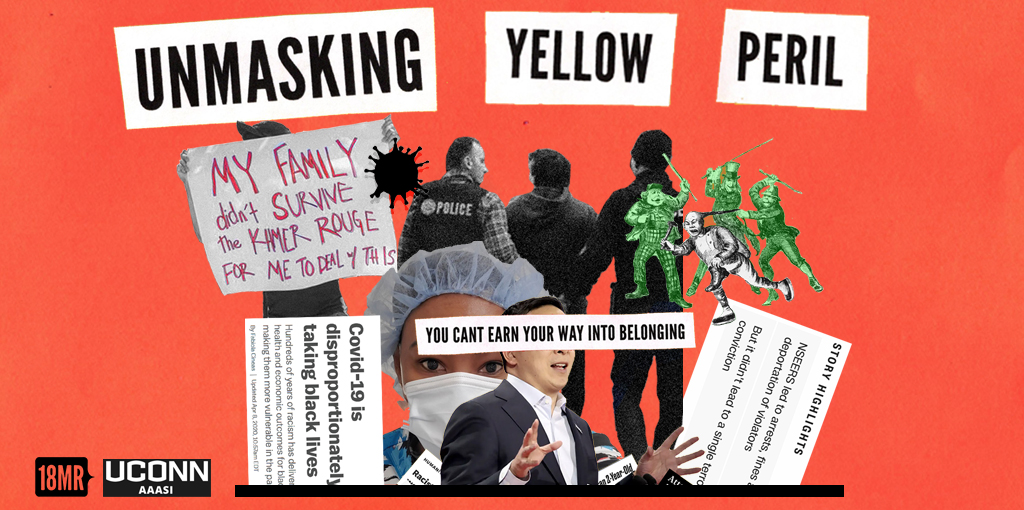

Not only do Asian Americans worry about surviving the virus, we also fear for our lives. Our loved ones are experiencing skyrocketing levels of unchecked hate and violence – over 100 hundred hate crimes a day. This violence is the latest iteration of Yellow Peril. It is a form of white supremacist settler nationalism that the U.S. pioneered to peddle racial fear and justify endless global war and the exploitation and expulsion of what they perceive as diseased and enemy Asians.

What we are experiencing in 2020 is tied to the violence of the mid-1800s when Chinese immigrants were targeted while risking their lives to lay railroad tracks. As a result of white suspicion and fear, the US passed racial bans on immigration and naturalization in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. This law created a new gold standard in settler states and made Yellow Peril a core element of US national identity.

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic fit the ready-made story of Yellow Peril in the US. Racist responses to the spread of the disease are consistent with a history of treating Asians as a foreign threat. Part of undoing the power of Yellow Peril is confronting the history of empire, capitalism, and white supremacy and building a vision of peace, justice, and health which celebrates and honors our interdependence.

Unmasking Yellow Peril is a collaboration between 18 Million Rising, the Asian and Asian American Studies Institute at the University of Connecticut, and Jason Oliver Chang, Associate Professor of History and Asian American Studies at the University of Connecticut. We seek to ground ourselves in the long history of Yellow Peril, uncover its many forms, and resist it in the time of COVID-19.

Yellow Peril has been here for more than a century, it’s time to unmask it.

The Perpetual Foreigners

Throughout history, the “perpetual foreigner” stereotype has meant that Asian Americans (and other people of color) have been denied the ability to be unquestionably American. When you’re seen as foreign, you’re seen as disposable and exploitable. This is not a casual discrimination but a deep seated bias that sustains capitalist exploitation. The proof is written into the labor history of Asian America.

In the 1800s, contracted laborers, known as “Coolies,” from Southern China and South Asia were exported to colonial plantations to replace emancipated enslaved Africans. The working conditions of coolies earned them a reputation as poor, dirty, and diseased. When other Chinese laborers migrated alongside the coolie trade, these stereotypes applied to them as well. In California during the Gold Rush and railroad boom, tens of thousands of Chinese arrived in North America. Despite generating enormous wealth at low wages, Chinese laborers were identified as a scourge of the American west by white labor unions and settler communities in the frontier.

At the turn of the century, American colonizers in the Philippines were waging a war not only against freedom fighters, but a war against what they deemed the uncivilized and diseased nature of Filipino people. Black soldiers were even sent to participate in the Philippine American War and were believed to have immunity to tropical diseases common there. Part of their “civilizing” work included American-style education such as nursing programs. Filipinos now make up the largest immigrant supply of nurses in the US, and are a critical frontline response to COVID-19, where they are dying due to lack of Personal Protective Equipment.

Today, many South Asian immigrants hold H1-B visas in the tech industry. Even though they hold temporary visas, they are permanent employees who earn less, pay taxes, and have no political rights – sending the message “we want labor, not neighbors.” They have been called “high-tech braceros” – a reference to the Bracero Program that brought millions of Mexican farmworkers into the US for temporary work from the 40s through the 60s. Now, with COVID-19 travel lockdowns and tech layoffs, many H1-B visa holders are living in uncertainty without a job and inability to return home.

During WWII, some Chinese Americans sought to distance themselves from the hate directed at Japanese Americans through buttons and signs. Today, we can see many Asian Americans proudly claim that they are not Chinese, and therefore not responsible for the “Chinese Virus.” Yellow Peril collapses Asian Americans into a monolithic foreign threat. Fear is a powerful tool of division. Our best response is to resist white supremacy and xenophobia in solidarity with one another.

YOU CAN’T EARN YOUR WAY INTO BELONGING. You belong because you’re here. Despite what Andrew Yang may say, Asian American patriotism and respectability politics will never end violent xenophobia in a time of COVID-19. White people are viewed as American not because they labored hard for it, but because the law is built on exclusion and subordination of people of color.

Yellow Peril + Placemaking

The imagined fear of a foreign threat is step one in the Yellow Peril playbook. The next, is often, the eradication of an enemy within. Our physical space determines how we survive. Notions of Yellow Peril have impacted Asian American communities and space throughout history and continues to be embedded in placemaking today.

In the late 1800s, over 100 settlements up and down the West Coast violently forced out their Chinese immigrant residents. Thousands of people were run out of town while rioting white mobs looted homes and businesses. Many of the spaces we may think of as “white” spaces are actually sites with a brutally erased Chinese American history.

Despite policies against their land ownership, Japanese farmers grew nearly 40% of California produce by 1940. Resentful of their success, white farmers seized the opportunity to support Japanese American incarceration during WWII in order to rid themselves of competition. By 1960, Japanese American farmers dropped to a quarter of their pre-war numbers.

Yellow Peril does not only impact East Asians. From the 1880’s, Bengali Muslim immigrants integrated into historically Black neighborhoods from New Orleans to Harlem in order to find community and opportunity in a time of restrictive immigration policies. Later, in the late 1970s and early 80s, Vietnamese refugees battled the Ku Klux Klan in Seadrift, TX, after white fishermen in the area felt threatened by their presence.

Fast forward to 2020: Yellow Peril erupts during the COVID-19 pandemic. Once again, Chinese Americans (as well as other Asian Americans) face blame for the “foreign” virus, racist abuse, and a rapid withdrawal of business in ethnic enclaves. Chinatown residents, already resisting gentrification and years of disinvestment, struggle to keep customers and survive.

But we cannot talk about racism during COVID-19 without talking about anti-Blackness. While Asian Americans are facing a rise in harassment and hate crimes, our oppression is not the same as the violence Black Americans experience. During this pandemic, Black people face racial profiling for wearing masks, on top of crushing disparities in COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths. Generations of systemic racism in the form of food deserts, low-wage work, environmental racism, redlining, and more continue to create dangerous conditions for Black Americans. No matter the space, they are profiled – even as frontline responders.

Also, prisons and detention centers are major incubators for viral outbreaks because Black and brown lives are considered expendable. Mass incarceration during COVID-19 is a death sentence. Prisoners and detainees, disproportionately poor Black and brown people, are denied soap, running water, and physical space. This is torture as prison staff and ICE officers infect people who are caged. As we write this, the infection rate on Rikers Island is 9.18% compared to New York City’s infection rate of 1.62%.

At the same time, many Indigenous communities are grappling with a lack of adequate medical care and basic necessities such as running water. The Navajo Nation has just 12 healthcare facilities in 27,000 square miles – and has lost more lives to COVID-19 than 13 states combined.

As Asian Americans, we must not only organize in our own spaces, but rise in solidarity with Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color as they mourn and fight for their lives.

Yellow Peril + Border Imperialism

Did you know that Chinese migrants were the first “illegal immigrants”? The original efforts to police the US-Mexico border were designed to keep Chinese immigrants out. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was the result of a national campaign to exclude Chinese people out of racist fears. Chinese immigrants resisted the ban by entering through the Southern border, forming connections with Mexicans along the way. The US responded by supplying special agents known as “Chinese Catchers” to find and deport those without documentation. These Chinese Catchers became the origins of the US Border Patrol, founded in 1924.

Decades later, after WWII Japanese incarceration ended, some of the fences previously used to keep Japanese Americans in, were reused to build the US-Mexico border wall and keep others out. The militarization of the border has always been connected to U.S. war making, including the fragmentation of indigenous Tohono O’odham land.

This early 20th century form of Yellow Peril border policing grew into the colossal apparatus we resist today: ICE raids in our communities, mass immigration detention, high-tech surveillance, vigilante violence, and more – usually deployed against Latinx immigrant communities. Every dollar spent on border policing has twice the negative impact, first by bringing violence into our communities and second by diminishing funding otherwise spent on social supports.

Anti-Asian pathogen racism has shaped immigration policing throughout history. Asian immigrants entering the US through Angel Island Immigration Station between 1910 and 1940 were often held indefinitely and subject to quarantine, disinfection, and invasive medical examinations. This treatment was replicated with Mexican braceros who were fumigated with the dangerous pesticide DDT upon entry to the US. Yellow Peril casts Asians as diseased in order to justify populist xenophobia, immigration restrictions, and denial of political rights. In the time of COVID-19, conservatives point to the “weak” border as a health threat, while ICE deports those infected with the virus.

Yellow Peril is a gruesome inheritance whose impacts reach across communities of color and through the generations.. The Chinese Exclusion Act initiated waves of restrictive immigration policies all the way to Trump’s Muslim Ban. But, our resistance to Yellow Peril can benefit all, such as the 1898 Supreme Court case of Wong Kim Ark, whose ruling created “birthright citizenship” in opposition to a nativist agenda that sought to exclude people of color.

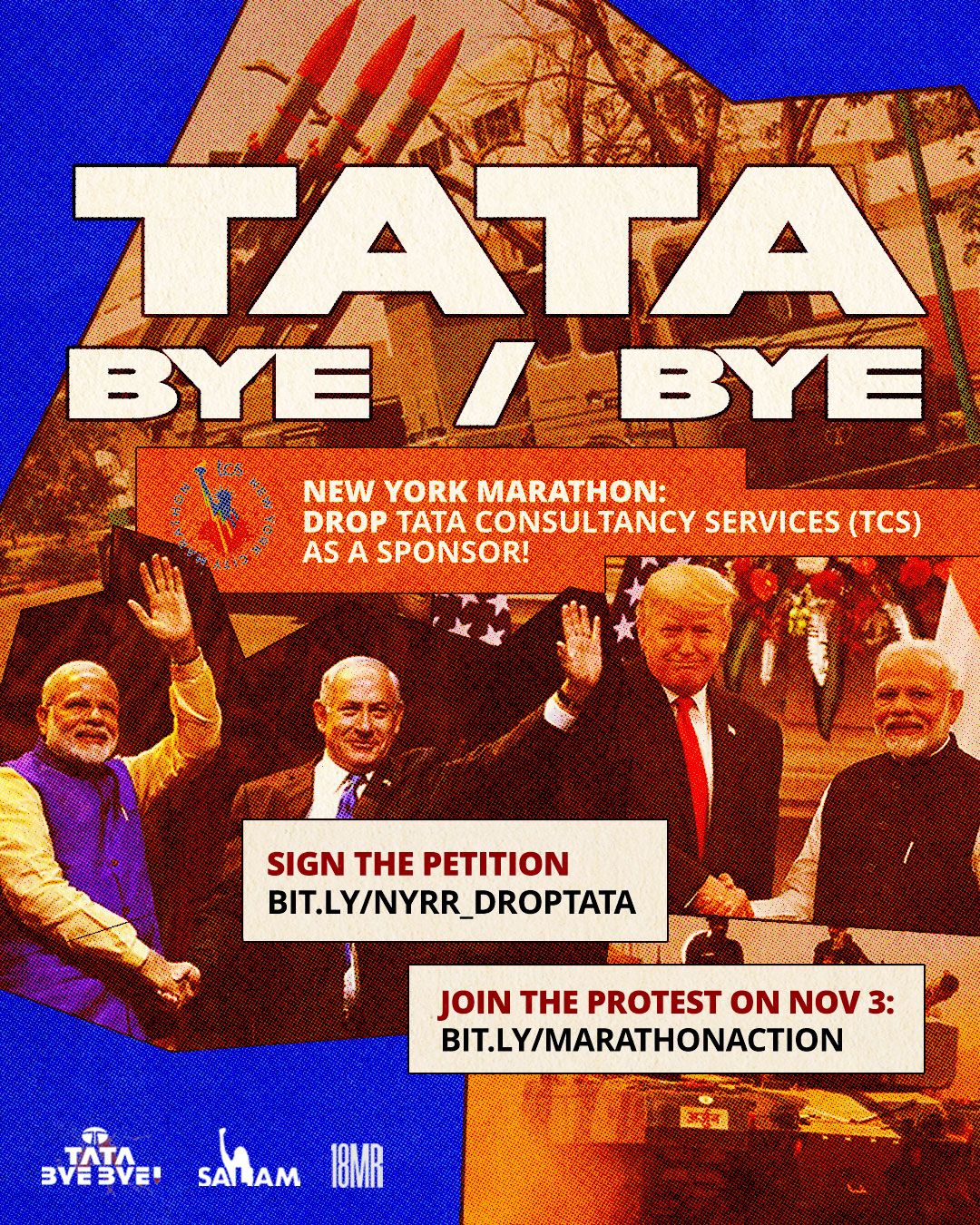

UPDATE 11/4/24 Download our FREE ZINE for you to print out, fold and distribute to your community. Though the Marathon is over, we still must inform […]

UPDATE 11/4/24 Download our FREE ZINE for you to print out, fold and distribute to your community. Though the Marathon is over, we still must inform […]