18MR has produced Fertile Ground, a beautiful illustrated botanical poster and accompanying essay that introduces the concept of abolition, provides analysis on our current moment in Asian America, the limits of #StopAsianHate, and examples of community resistance to police violence.

When you purchase your Fertile Ground print today a portion of the print proceeds will support the Southern, abolitionist organizing work of SEAC Village.

You can also access a free digital download here.

Today, Asian Americans are facing a surge, within a long history, of racism and violence. We’ve seen the tragic headlines and footage, and felt the fear in our Asian American communities since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. From attacks on city streets to two mass shootings in Atlanta and Indianapolis within weeks of each other, we are experiencing acute harm across the country. In response, countless Asian Americans and allies have used the hashtag #StopAsianHate to spread awareness about anti-Asian attacks. The slogan and hashtag have reached millions as a call to action. This demand for the state to protect us is as much a survival strategy as it is a fight for our dignity and belonging in the U.S.

Many Asian Americans, including celebrities and elected officials, have also turned to policing and hate crime laws as solutions to the attacks and discrimination. However, we know that if funding the police made Asian Americans safe, we’d already be safe!

Police have spent years asking for more and more funding in the name of public safety, reforms, and anti-bias and cultural competency training. They say their intention is to make policing kinder, gentler, and more effective. The U.S. already spends approximately $180 billion every year on policing and incarceration. And yet, for years, our communities have lived with racial violence – including at the hands of police. That’s because many reforms end up putting more funding into the police in order to implement change, restructure, or conduct training in ways that increase police presence in marginalized communities. We cannot reform this institution to be safer for any of us.

At this moment, our broader Asian American movement is faced with a decision. Will we keep a privileged few among us safe through hate crime laws and increased policing or will we fight for true safety and freedom for all of us?

Our continued investment in a punishment system that kills, cages, and surveils people in the name of safety dehumanizes all of us. In our hearts, we know we must choose life. We must move toward abolition.

Abolition is a movement to end policing and incarceration. It is a long-term process to reorganize our society and create systemic change so that prisons are obsolete. It is the work to shift funding, resources, power, and responsibility away from police and into community-based safety alternatives. Abolition is not only about dismantling, it is also about creating. As Ruth Wilson Gilmore says, “Abolition is about presence, not absence. It’s about building life-affirming institutions.”

In our current system, we are asked to believe the ‘reasonable’ choice is punishment, cages, and death. When we’ve caused harm, are harmed, or are perceived as inherently harmful, our choices for repair and healing are gravely limited. Hate crime laws, calling the cops, convictions. All these false solutions point to our own annihilation.

Abolition is the fertile ground beneath us and between us. Yes, abolition is what emerges between us. It’s not a top-down thing, a savior, or one policy to free us all. It’s us, hand in hand, creating and practicing new ways of being. This is why it is a transformative living practice. We literally grow it, together.

Abolition does not mean replacing the police with another simple solution. It requires a deep diversity of strategies to grow safer communities. Growing abolition comes with making mistakes, experimenting, and being with uncertainty. We can say no to the prison industrial complex, without having all the answers and solutions. We are learning as we go.

In spite of these challenges, we choose abolition and we choose life. By partnering with the land, we begin by listening to these plant guides who teach us how to move beyond a “stop hate” frame and towards a new path. This is a living map for ourselves and other Asian Americans who want to tend the fertile ground of abolition.

Beyond the Hate Frame

Asians have been treated as a foreign threat since we first arrived in the so-called United States. But, the language and framing of “Stop Asian Hate” limits our understanding of anti-Asian racism to individual violent attacks or acts of discrimination during the pandemic. In reality, anti-Asian racism and violence have come in many forms throughout history:

- U.S imperialist wars and colonization across Asia, from the Korean War to the colonization of the Philippines, to the Vietnam War, which led to Asian death and displacement

- The absence of Asian American history in school curricula, which erases both our historic struggles against racism, as well as our contributions to the shaping of this settler-colonial country

- Xenophobic policies from the Chinese Exclusion Act to Japanese American incarceration during World War II, which have reinforced the notion that Asian Americans are perpetual foreigners

- The detainment and deportation of Southeast Asian immigrants and refugees by ICE, which separates families and contributes to mass incarceration

- The surveillance, deportation, and incarceration of South Asians and Muslims during a wave of Islamophobic policingand war-making in the post-9/11 era

- Exploitative and imperialist economic policies and trade agreements, which contribute to Asian labor exploitation and resource extraction for the benefit of the Global North

- Lack of universal healthcare, housing, and other social services that would combat the widest wealth gap of any racial group in the US

By focusing on individual “hate” incidents, the #StopAsianHate frame means that we cannot address these forms of systemic racism against Asian Americans. And what counts as “hate” anyway? Many people use the term “hate crime” to loosely mean a hateful, biased incident. But hate crimes have specific legal definitions that are regulated by the state. As Asian Americans, we refuse to use state definitions of racism and bias when the U.S. is a major source of racism against us. Especially when the FBI’s own data on hate crime “offenders” reveal these laws are used to disproportionately criminalize Black people.

During the pandemic, many Asian Americans expressed support with #BlackLivesMatter, a movement that advocates for abolition and defunding the police. But, with little to no community-based safety options, some of those same people turned to cops to #StopAsianHate. Some Asian Americans have also demanded punishment and convictions for those who cause harm by circulating cash rewards for arrests and supporting hate crime sentencing enhancements.

We cannot find justice for Asian Americans within a system that we know is unjust and violent toward Black people. Creating freedom from violence beyond police requires all of our creativity, resourcefulness, and investment in transformation. What Asian Americans choose to create and practice right now will be the blueprint for not just what keeps us safe, but how we collectively get free.

We can create deep, holistic change when we face the root causes of the harm we experience. The system was built this way – it perpetuates a vicious cycle of harm. We’re ready to grow beyond it.

Networks of Resistance

Policing and the larger prison industrial complex are, in the words of Mariame Kaba, “death-making institutions.” They do not repair, heal, or generate safety for communities – just the opposite in fact.

Since its founding as an institution rooted in “slave patrols,” U.S. law enforcement has been a source of violence, oppression, and surveillance for Black people. Policing also sits at the intersections of misogyny, homophobia and transphobia, ableism, Islamophobia, capitalism, whorephobia, and other systems of oppression. Our comrades often cannot turn to police due to this systemic prejudice. As an Asian American community, we can learn from the work and words of those who have had no choice but to find safety outside the system.

The trans women of color, Sylvia Rivera and Masha P. Johnson, behind Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) are an example of creating safety when one cannot rely on the state or wider community for resources. In order to survive in a world that criminalized their very existence, Sylvia and Marsha did sex work. Marsha claimed to have been arrested over 100 times. They used their earnings to found STAR House, a building in NYC, in 1970 where they provided shelter and protection to queer and trans youth who would otherwise be unhoused. They built a network of care and resilience in the face of systemic exclusion, and a path to safety where there was none.

Decades later, the Sylvia Rivera Law Project spoke out against the use of hate crime legislation to “protect” queer and trans people. They stated, “As we see trans people profiled by police, disproportionately arrested and detained, caught in systems of poverty and detention, and facing extreme violence in prisons, jails and detention centers, we believe that this system itself is a main perpetrator of violence against our communities.”

We know that Asian American women who engage in criminalized and stigmatized labor, including in the sex industry, are harmed daily by police harassment and criminalization, marginalization, and racial profiling. The perceived “victimhood” of women workers has also been used to justify harsh immigration, anti-trafficking, and criminal policies. It’s no coincidence that the first restrictive federal immigration law in the U.S., the Page Act of 1875, targeted Chinese women due to orientalist fears around sexuality and sex work. This law set off immigration exclusion for years to come.

Red Canary Song formed in 2017 after the death of immigrant massage worker, Yang Song, during a police raid on her work place in Flushing, Queens. We look to organizers like RCS for lessons on how to support Asian massage and sex worker safety and empowerment. As it turns out, sex worker activists don’t want to be “rescued” from their work by police, they want their work to be decriminalized.

Many in our community are calling to defund the police and reinvest in mental health support and social services for those who have attacked Asian Americans. We turn to disability justice organizers for their analysis on the ways policing and ableism intersect to create conditions in which half of people killed by law enforcement are disabled. They have taught us that abolition does not stop at ending police and prisons, but requires us to root out carceral thinking and systems wherever they may be. This means abolishing psychiatric incarceration and the policing of neurodivergence and disability by mental health systems. We must ensure that the alternatives to incarceration we support do not replicate the policing we are working to end.

In spite of these realities, Asian Americans have often chosen respectability politics over solidarity with those who are impacted by police violence. Respectability politics use narratives of Asian conformity, morality, and our alignment with dominant systems to try to “win” social acceptance and political power. That it is better for Asian Americans to become cops than it is to dismantle policing. That it is more advantageous for us to uphold white supremacy than to resist it.

In 2014, NYPD Officer Peter Liang shot and killed Akai Gurley, a 28 year old Black man, who had been visiting his girlfriend and getting his hair braided. Liang’s attorney claimed the officer did not provide medical aid after the shooting because he was “so upset.” Conservative Chinese Americans rallied to support Liang – not the Gurley family and activists seeking accountability for murder. This alignment with the carceral state shows us the limits of organizing solely around our identity as Asian Americans instead of around and across shared values of justice.

Our imagined “safety” cannot come at the expense of Black lives. As Asian Americans, abolition means turning toward one another and building a united vision for community safety that includes all of us. We must build networks of care and healing to make this vision real.

“Fertile Ground” Organizing Together

We want our family members and our communities to be safe from violence. But we know that prisons are part of a punishment system that does not heal people or transform the root causes of this violence. What do we want to build instead? And, how should we respond to Asian American calls for more police and prisons?

- We believe in listening and affirming the fears of our community members who rightfully want safety and protection from violent attacks. When we listen with love and empathy, we break through isolation and help identify ways we can create more safety through resources and community support.

- We dispel myths about who is most likely to be violent or racist against us. Narratives spread on news media and social media are often based on anti-Black racism and ableism instead of real data.

- We resist the belief that cops keep us safe and hold people accountable. In recent attacks against Asians, the police did not prevent violence; they showed up to respond afterward. Reporting a crime usually does not lead to an arrest or a conviction. In fact, data shows that only about 2% of “serious crimes’’ end in a conviction.

- We collaborate with our diverse communities to build solidarity, divest from police, and create alternatives through community-based safety resources.

- Supporting movements to reallocate police funding to community needs such as healthcare, housing, and schools, and reduce contact with police. Examples of this are: Durham, NC’s 10 to Transform Campaign, which would transfer 10% of police officer positions to unarmed, cop-free 911 responders.Freedom Inc.’s Cop Free Schools Campaign which brought together Black and Southeast Asian youth to end a contract that funded police presence in Madison, WI high schools. Anti Police-Terror Project’s MH First Hotline, a new model of response to mental health crises in Oakland, CA.

slug: mh-first-oakland), a new model of response to mental health crises in Oakland, CA. - Developing safer communities through relationship building and a strong public presence, such as Oakland’s Chinatown Community Ambassadors Program.

- Providing harm reduction programs that affirm our agency and wellness over stigma and criminalization.

- Supporting movements to reallocate police funding to community needs such as healthcare, housing, and schools, and reduce contact with police. Examples of this are: Durham, NC’s 10 to Transform Campaign, which would transfer 10% of police officer positions to unarmed, cop-free 911 responders.Freedom Inc.’s Cop Free Schools Campaign which brought together Black and Southeast Asian youth to end a contract that funded police presence in Madison, WI high schools. Anti Police-Terror Project’s MH First Hotline, a new model of response to mental health crises in Oakland, CA.

- We refuse false solutions through policy reforms that end up entrenching police and prisons instead of dismantling them and causing further harm.

- We challenge ourselves to listen and shift when what we think keeps us safe actually harms others. We must practice being in debate, disagreement, and principled struggle in order to build a new world.

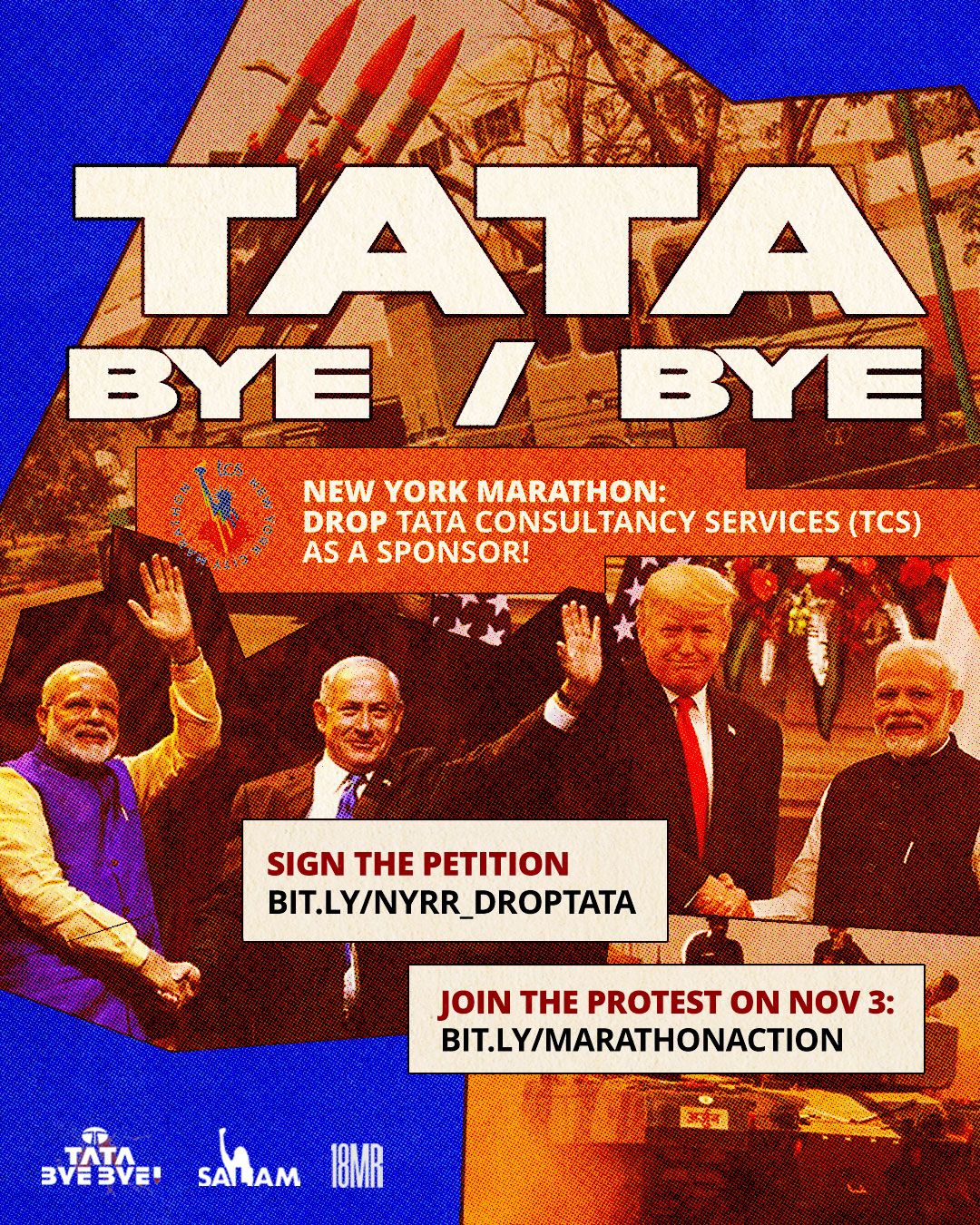

UPDATE 11/4/24 Download our FREE ZINE for you to print out, fold and distribute to your community. Though the Marathon is over, we still must inform […]

UPDATE 11/4/24 Download our FREE ZINE for you to print out, fold and distribute to your community. Though the Marathon is over, we still must inform […]